Routes and Ports

Finnafjord:

a new port for the melting Arctic

New joint venture the Finnafjord Port Development Company is planning to build a new deepwater port at Finnafjord in northeast Iceland, as warmer waters make year-round Arctic shipping increasingly viable. Chris Lo speaks to pProject partner Bremenports to discuss the opportunities and environmental sensitivities around this new development.

All images courtesy of Bremenports

“Currently, we do not

see the Northern Sea Route as a viable commercial alternative to existing east-west routes,” said A.P. Moller Maersk chief technical officer Palle Laursen at the end of September 2018. This was after the company’s ice-class Baltic feeder vessel Venta Maersk successfully navigated the shipping lane running along Russia’s northern coast to deliver frozen fish to St. Petersburg from Vladivostok, all without an icebreaker escort. “Today, the passage is only feasible for around three months a year which may change with time.”

‘Change with time’ might be the most important phrase in Laursen’s statement, especially for those industry observers with a particular interest in the emerging possibility of year-round shipping across the Northern Sea Route and the Northeast Passage, which would dramatically cut the transit time between North America, Europe and East Asia when compared to the traditional east-west route via the Suez Canal.

Arctic shipping heats up

As with the world’s first unescorted voyage through the route in 2017, made by Sovcomflot’s gas tanker Christophe de Margerie, Maersk’s successful trial won’t spawn a northern shipping rush overnight. It does, however, highlight the trend of diminishing Arctic sea ice, a process that is expected to continue and accelerate in the coming years. The Russian Ministry of Transport predicted in 2017 that cargo along the route would rise tenfold (from an admittedly low base) by 2020.

To many observers, the rapid melting of Arctic sea ice is emblematic of the most worrying trends in the climate change crisis. To large shipping companies, it also represents an opportunity to make huge savings on their international routes, both financially and environmentally.

The acceleration in the loss of Arctic ice is unlikely to be reversed.

“Even if we stopped greenhouse emissions tomorrow, the acceleration in the loss of Arctic ice is unlikely to be reversed,” University of Southampton earth and ocean science principal teaching fellow Dr Simon Boxall told the Guardian in 2017. “The irony is that one advantage of climate change is that we will probably use less fuel going to the Pacific.”

As shipping routes through Arctic waters continue to open up, the industry is increasingly preparing to make the most of it, including building a new generation of icebreakers and ice-capable vessels. As well as the right ships, higher shipping volumes in the Arctic will bring the need for new supporting infrastructure.

“The ice is melting quicker each year, and the shipping routes will change,” says Holger Bruns, spokesman for Bremenports, which manages the ports of Bremen and Bremerhaven in north-western Germany. “You will need about ten days less from China to America, for example. It’s high time to establish infrastructure in the region that is necessary for safe shipping routes.”

Holger Bruns, spokesman for Bremenports.

Image courtesy of

Laying the groundwork for a new Arctic port

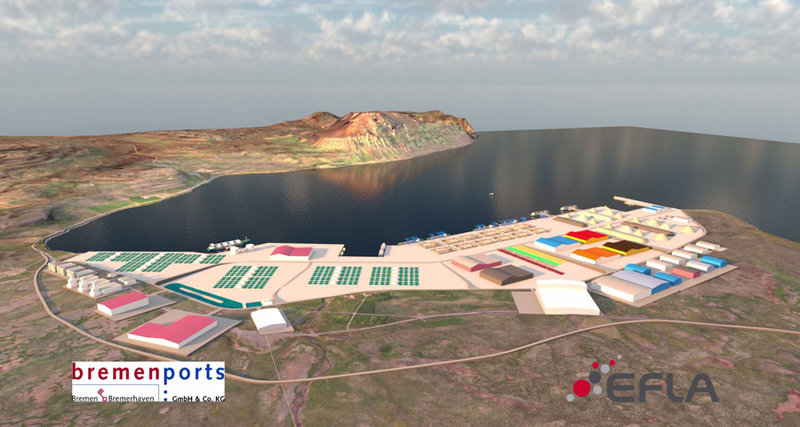

With this goal in mind, in April this year Bremenports signed a joint venture agreement with Icelandic engineering consultancy EFLA, along with the local municipalities of Langanesbyggð and Vopnafjarðarhreppur, to develop a new port in the Finnafjord area of north-east Iceland.

The port is expected to be built between 2021 and 2023.

The port, which is expected to be built between 2021 and 2023 with operations to continue until at least 2040, is currently in the preparatory development stages. Once built, its partners intend that it will become a much-needed port hub to drive the sustainable development of Arctic shipping in the region.

Bremenports’ involvement in the project began around 2014 after a request from EFLA, which has been doing feasibility work on the Finnafjord project since 2007 at the behest of central and local governments in Iceland. Bremenports signed a memorandum of understanding with its Icelandic partners in 2014, and its own subsequent feasibility studies convinced the company to move forward, leading to this year’s joint venture agreement and the formation of the Finnafjord Port Development Company (FFPD).

Diversifying economies

Currently, Bremenports owns a 66% stake in the joint venture, while EFLA owns 26% and the two Icelandic municipalities take the remaining 8% share. For Bremenports, the deal reflects an increasing tendency to offer its expertise internationally as well as managing the Bremen/Bremerhaven port group, but the Finnafjord Port Project represents the biggest step on to the international stage by far.

“We have some more international projects, but the Finnafjord development is by far the biggest and most important one,” says Bruns. “There’s no second project like this.”

The port project is a possibility to develop the region on a broader base than it is now.

From the Icelandic authorities’ perspective, the port represents a golden opportunity to diversify the regional economy. The three villages nearby Finnafjord – Thorshöfn, Vopnafjord and Bakkafjördur – accommodate a total of just 1,300 people, who are almost entirely dependent on fishing for their livelihoods.

“[The municipalities] worry that they will end up with a problem in the fishing industry because the fish are going much further away from Iceland, and if the fishing industry doesn’t work, they have nothing they can live on,” Bruns explains. “So the port project is a possibility to develop the region on a broader base than it is now.”

Finnafjord: the ideal spot for an Arctic shipping hub?

As well as providing general services as a regional Arctic transshipment hub, the Finnafjord port also has the potential to improve safety in the surrounding waters as northern shipping routes continue to get busier.

“Today there’s no port [in the region] for search-and-rescue, so Finnafjord can take an important role for sustainable development in the Arctic region,” says Bruns.

So after years of feasibility studies what makes Finnafjord the right location for an Arctic port in Iceland? Research previously undertaken by Icelandic public bodies in 2007 and 2008 confirmed to the partners the site’s fundamental strengths.

Finnafjord can take an important role for sustainable development in the Arctic region.

The project’s location on Iceland’s north-eastern tip in the Bakkaflói Bay is sheltered by the Langanes peninsula, which protects it from wind and waves, the latter of which reach around two metres. Government research revealed that even in the worst-case scenario, a once-a-century wave hitting Finnafjord would be lower than a once-a-year wave near the capital of Reykjavik. The bay is similarly protected from sea ice, little of which ever reaches Iceland’s shores, but if it does drift to Iceland from the coast of Greenland, the Langanes peninsula prevents it from reaching any further south.

The water in the harbour is 20m deep, making Finnafjord viable as a deepwater port, and the isostatic changes to the shoreline have created a flat hinterland behind the harbour. The formerly subsea gravel on this land, Bremenports says, will be suited to use in construction and concrete production.

Image courtesy of

Economics and environment: next steps for the Finnafjord Port Project

The FFPD partners are expecting to attract a new investor on the project by the end of 2019; Holger says the new player will take a portion of Bremenports’ share in FFPD and provide financing for the next phase of port planning, leading up to the expected construction start date in 2021.

The Finnafjord site has ample space for the construction of 6km of quays and the development of 1,200 hectares of hinterland. The port will be developed under a build-operate-transfer (BOT) model, meaning that concessionaires that bid successfully to operate out of the port will assume the full costs of constructing the quays. Work to create a business case to bring these partners on board is ongoing.

“The next step will be to develop a financial motive for the project, and we are just working on this,” says Bruns.

The next step will be to develop a financial motive for the project.

Given that climate change is the damaging process that created the Finnafjord opportunity, and the environmental sensitivity of the surrounding marine area, FFPD has insisted that the port will be developed according to the most stringent sustainability criteria, facilitated by Iceland’s abundance of carbon-free geothermal and hydroelectric power. Holger also notes that hydropower could also make Finnafjord a hub for green shipping fuels in the region.

“We have to have zero emissions; there must be no carbon footprint,” he says. “We want to develop hydro energy for the shipping of the future, so there will be a lot of good impacts for sustainable development in the region. The planning in detail will start next year, and then we have the next five to eight years, I think, to develop this big project and the environmental impact will be a very important part of the planning. It will be a sustainable port or there will be no port.”