Crew

The next generation:

how technology is driving ship cadet training

Training ships have provided an opportunity for cadets to gain the skills they need for more than 150 years. Andrew Tunnicliffe looks at how technology has revolutionised the training vessel, and how training standards must now catch up.

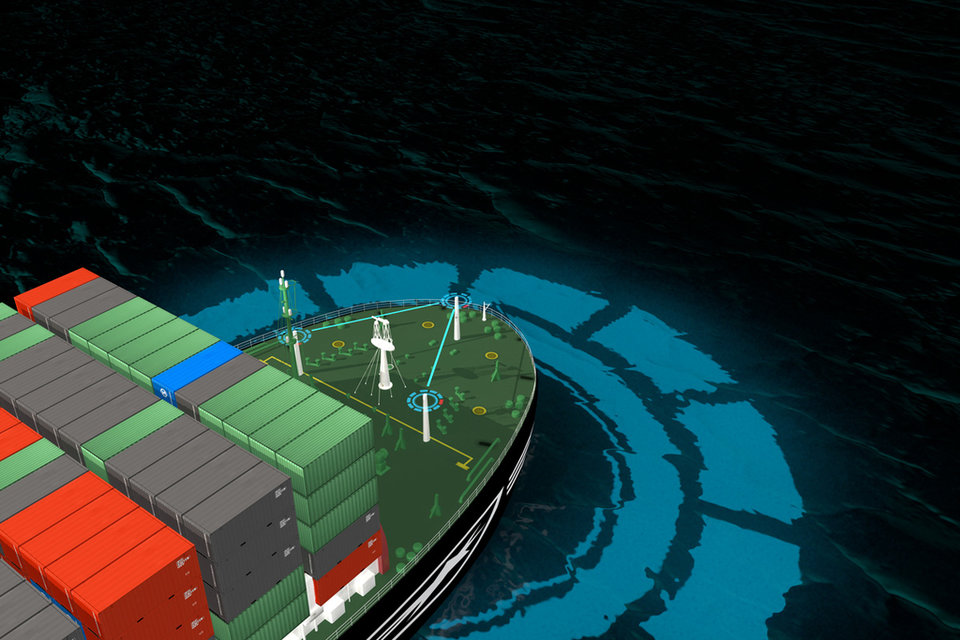

Image:

Two-time US President

Grover Cleveland once proclaimed that “in calm water, every ship has a good captain”. Today we know this not to be true; the tragic capsizing of the Costa Concordia in 2012 is testament to that. The reality is, even the best captains can find themselves challenged in the calmest waters.

Although it is likely not true to say for all, many of the world’s best captains and crew are so because of their experience, all underpinned with exceptional training. Some of that training is undertaken aboard training ships, a mainstay of any ship captain or helmsperson's training career. These ships allow those looking towards a career on the water the opportunity to experience the environment and hone their skills.

The prospect of allowing people to set sail with at least some vessel experience is so highly regarded, the British Navy commissioned HMS Implacable towards the end of the industrial revolution in the 1850s. Walking its decks back then would have been nothing like the experience that can be gained aboard today’s training fleet.

The next generation of training vessels

In April 2020, a flurry of contracts were announced, heralding the next generation of training vessels. The ships will be furnished with the latest technologies, introducing students to a future onboard. STC Group announced an agreement with Dutch-based shipbuilder Concordia Damen. The contract is for a new, sustainable training vessel; named Ab Initio, it will replace two ageing training ship-based facilities used by the training institution for more than half a century.

Just days later, US-based shipbuilder Philly Shipyard was awarded the contract to build a fleet of training vessels on behalf of the United States Maritime Administration (MARAD). In a statement, Transportation Secretary Elaine L Chao said: “This new world class vessel, constructed at an American shipyard, is part of our much-needed programme to replace the ageing training vessels currently operated by state maritime academies.”

The NSMV is designed to provide a state-of-the-art training platform

The National Security Multi-Mission Vessel (NSMV) will have capacity of around 600 cadets at any one time, but it can also be configured to respond at times of crisis such as natural or humanitarian disasters. MARAD said: “The NSMV is designed to provide a state-of-the-art training platform that ensures the US continues to set the world standard in maritime training. The ship is outfitted with numerous training spaces to include eight classrooms, a full training bridge, lab spaces and an auditorium.”

STC Group’s Ab Initio will be used to train across a spectrum of different grades, from preparatory to higher professional education. “We are honoured that the renowned Concordia Damen shipyard is enthusiastic about taking on this challenging project with us,” said board member Jan Kweekel. “From now on we will work together on building a future-proof and state-of-the-art training vessel.”

Sustainability was one of the biggest considerations when designing the vessel. As well as solar panels, it boasts a hybrid diesel-electric propulsion system and battery pack among its environmental credentials.

An artist’s impression of the Ab Initio. Image: STC Group / Concordia Damen

Image:

Reshaping the training environment

Technology is having a significant impact on the role of captains, as it is in countless other professions. It is no surprise that the common theme running through this newest fleet of training vessels and their specification is the emphasis on ensuring they are tech heavy, thereby “future-proofing” them as STC Group put it. But technology is not just breaking into the at-sea training sphere.

Although simulation has been used for some time, the concept of “digital twinning” – building onshore systems that almost completely replicate the experience of the real-life vessel – is gaining in popularity. Not only will this benefit those new to the profession who can add their experience to their training record book, but it also has a role in training already established captains and crew. This can be a significant resource, for example, ahead of the delivery of a new vessel, meaning many manhours can be spent abroad, virtually, before a ship ever sets sail.

Although simulation has been used for some time, the concept of “digital twinning” is gaining in popularity

Such efforts are not only afforded to captains and bridge crew. Finnish-owned Wärtsilä has been working with training providers to ensure their technologies are as up-to-date as possible, staying in step with other marine technologies and practices. Combined with other simulation capabilities and technologies, future crew can gain experience and marry class-based teaching with the skills practical learning can offer.

The digitisation of some elements of training has been ongoing for a while too, although for many in the profession it has been too slow. This is particularly true of the journey cadets take – for instance, the development of electronic training record books – and training standards they aspire to.

Wärtsilä’s LNG bunkering simulator. Image: Wärtsilä

Are standards sufficient?

In late 2018, International Chamber of Shipping chairman Esben Poulsson raised the issue. Speaking at an event in the Philippines, he said there needed to be a far-reaching review of the global convention on Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Seafarers (STCW). He said that the Convention “as currently drafted is still fit for purpose in the 21st Century” but change was needed.

“A fully revised STCW regime would allow the industry to adapt much more effectively to technological developments, including increased automation,” he said.

“It should provide a structure of sufficient flexibility to hit the moving target of a changing world fleet, and may need to develop a more modular approach to competency accumulation and certification. The arrival of new technology is already changing the functions that seafarers perform on board, and the skills and training they require.”

A fully revised STCW regime would allow the industry to adapt much more effectively to technological developments

Originally introduced in 1978, STCW has been revised several times since. However, the dramatic changes the profession has seen, largely the result of technological innovation, have not quite been reflected. The biggest revision came in 1995, with a smaller update 15 years later; there has been some revision in the interim, but nothing significant.

“With the involvement of all industry stakeholders, we think the time is now right to consider the next comprehensive revision of STCW akin to that completed by IMO Member States back in 1995,” Poulsson said.

New training standards should accommodate tech developments, such as automation.

Cadet training after Covid-19

The Covid-19 pandemic has, not surprisingly, had a significant impact on those currently going through their training. But like other industries, it may present an opportunity to overhaul at least some of the elements of training provision as the world looks to a future with the virus.

UK-based Clyde Marine Training said it had introduced digital classrooms to ensure training could continue. The company’s general manager, Katy Womersley, said the hope was the digital classrooms would keep cadets engaged and motivated. “The positive outcome of this difficult situation is how adaptive and forward-thinking all involved parties have been,” she added.

New technologies determine the requirements of the role, and for the most part this reality has driven the evolution of training

The industry has long accepted that new technologies will shape its future – from training to operations. New technologies determine the requirements of the role, and for the most part this reality has driven the evolution of training. It seems, however, as Poulsson argued in 2018, that change isn’t coming quickly enough. Like many other sectors, the current pandemic may help to address that imbalance.